Josephai “Babu” Elias, in Kadavumbhagam Synagogue’s prayer hall.

The Last Jews of Cochin, India: Their numbers are dwindling in a seaside town that once gave them refuge--but their culture remains.

Full story for Pacific Standard here.

Sarah Cohen, 95, one of five remaining Paradesi Jews in Mattancherry, Cochin, in her bedroom. Every morning, she enjoys a range of Kerala and Jewish dishes (dosa, idli, challah bread) and then spends the majority of her day sitting by the window, singing prayers and people-watching.

Sarah Cohen with her caretaker Thaha Ibrahim, a Muslim, (left) and her cook Celine Xavier, a Catholic (right).

Thaha Ibrahim in the doorway of Sarah’s embroidery shop. On his right is an embroidered map of India, encapsulating the unique mix of Jewish and Indian influences in the shop. A Muslim, he became interested in Judaism as a boy helping his uncle sell postcards outside of Cohen’s shop. “Sarah never had children,” he says, “so I’m her children.”

Paradesi Synagogue, India’s oldest active synagogue, sits at the end of Mattancherry’s “Jew Town.” With the Jewish community dwindling in Mattancherry, the synagogue’s main visitors are now tourists, who arrive during opening hours, between 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day except Saturday.

Paradesi Synagogue, quiet after a day of tourists bustling in and out. At the front of the building, a sign asks visitors to remove their shoes before entering. Entering a synagogue barefoot is not a common Jewish practice; it's adopted from Indian traditions.

The last tombstone left standing in a Jewish cemetery in Mattancherry. Residences and streets were built on the cemetery over the last 50 years, reducing its once-impressive size.

Kadavumbhagam Synagogue peeks out from behind thick green vegetation. Josephai “Babu” Elias transformed the front room of the synagogue into a plant and fish nursery when he took the building into his care in 1977.

Fish swim in neon blue tanks just in front of Kadavumbhagam Synagogue’s glittering prayer hall.

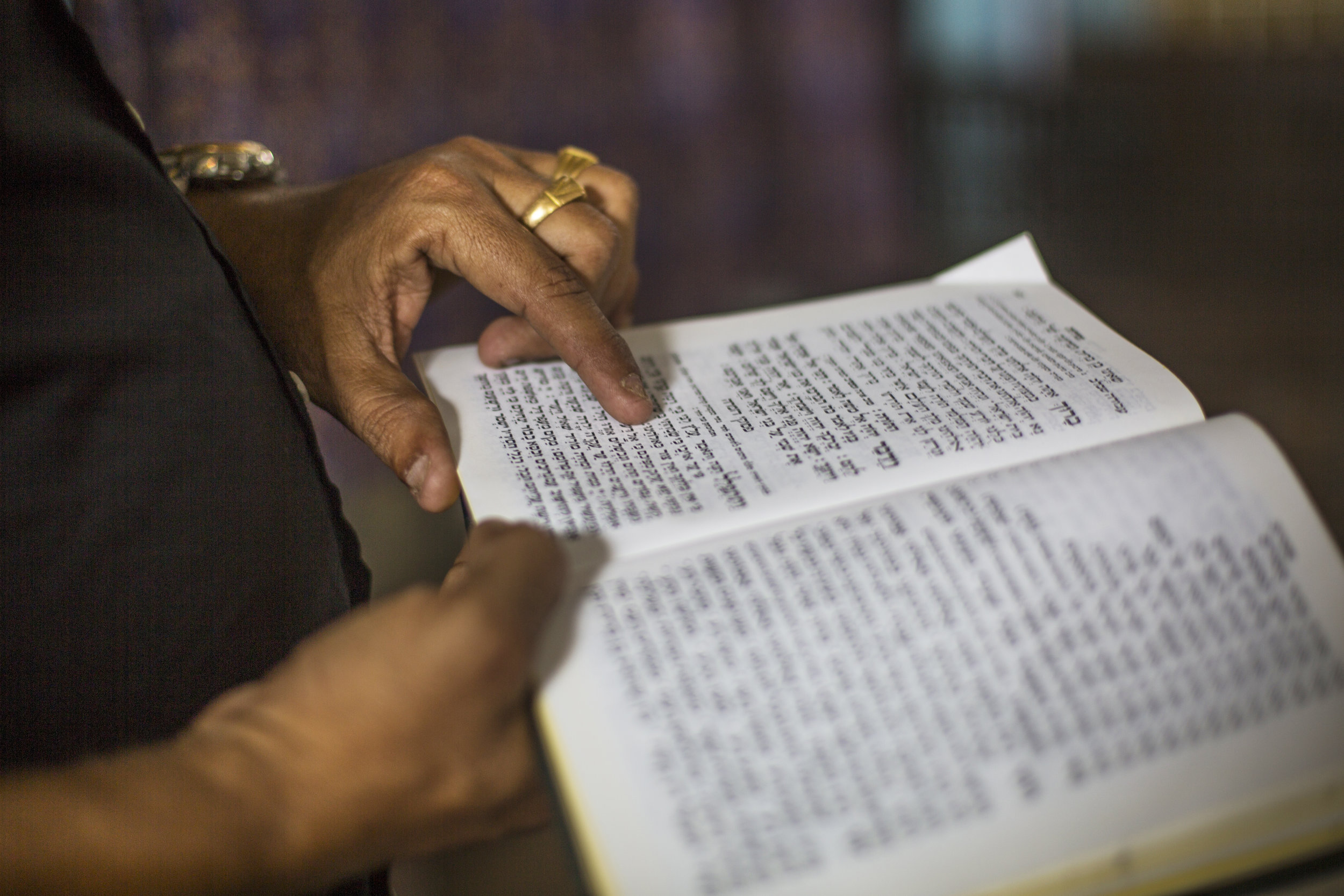

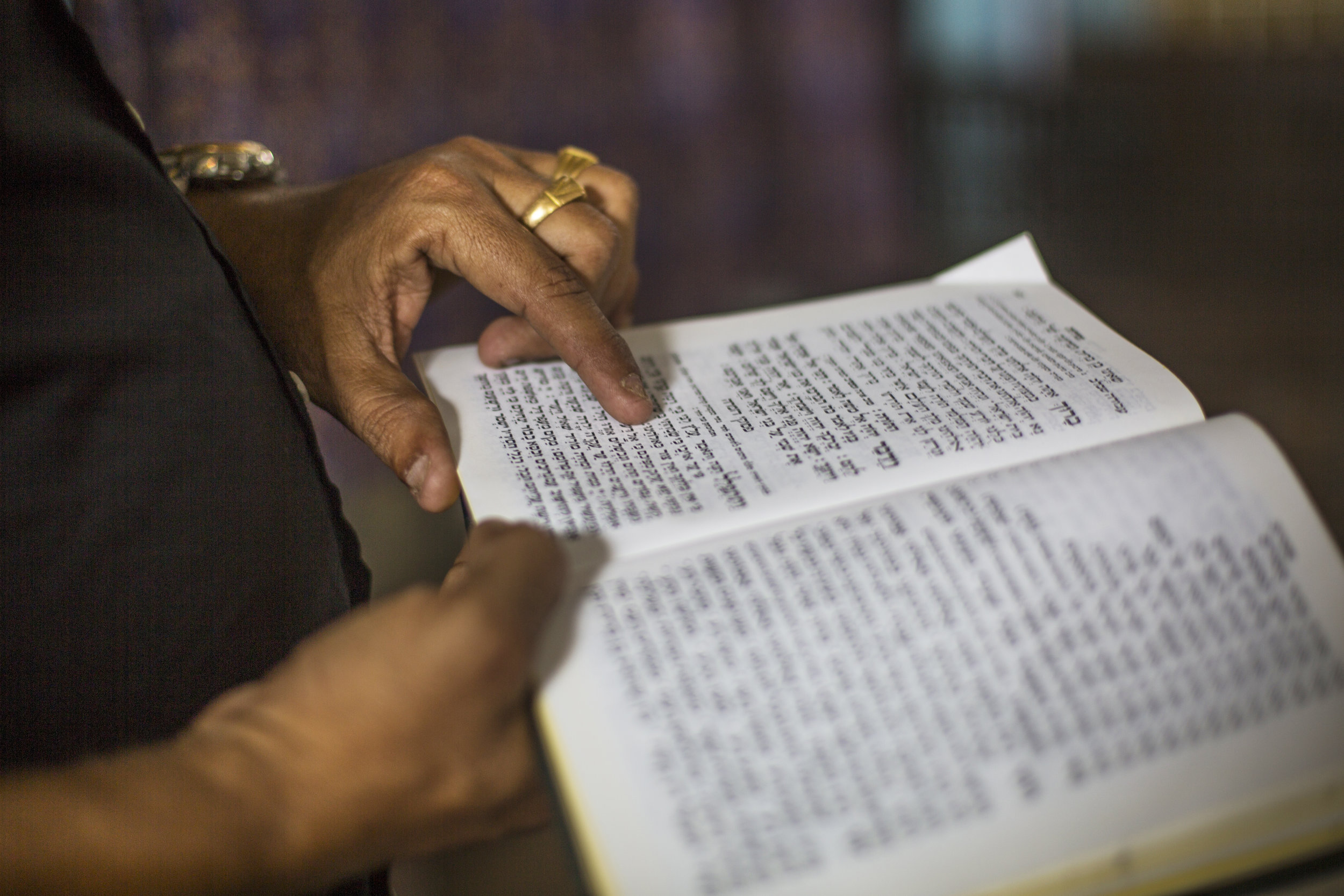

Babu opens his prayer book and starts singing the prayer he said his grandmother made him sing before breakfast every morning. “We had to sing from here,” he says, turning three pages, “to here. And only then we could have breakfast.”

Ofera Elias, Babu’s wife, stands at her grandmother’s grave in the Ernakulam Jewish Cemetery. She points out the weeds growing tall around the tombstones. “No one is taking enough care of this site.” She says that in the absence of a Jewish community, she and Babu have made their own community of Hindu and Muslim friends.

Professor Karma Chandran stands in the empty Mala Synagogue, 50 kilometers from Cochin. He is fighting to preserve the Mala Synagogue and Jewish cemetery, two sites that have been heavily neglected for decades. When the Mala Jewish community migrated to Israel in 1955, they made a written agreement with the local government to protect the sites, but in 2012, the local government made plans to build a stadium on cemetery land anyway. Now, the blue-and-red stadium looms over the remaining tombstones, the stadium left empty and half-constructed because of ongoing court cases between the government and the departed Jewish community.

Josephai “Babu” Elias, in Kadavumbhagam Synagogue’s prayer hall.

The Last Jews of Cochin, India: Their numbers are dwindling in a seaside town that once gave them refuge--but their culture remains.

Full story for Pacific Standard here.

Sarah Cohen, 95, one of five remaining Paradesi Jews in Mattancherry, Cochin, in her bedroom. Every morning, she enjoys a range of Kerala and Jewish dishes (dosa, idli, challah bread) and then spends the majority of her day sitting by the window, singing prayers and people-watching.

Sarah Cohen with her caretaker Thaha Ibrahim, a Muslim, (left) and her cook Celine Xavier, a Catholic (right).

Thaha Ibrahim in the doorway of Sarah’s embroidery shop. On his right is an embroidered map of India, encapsulating the unique mix of Jewish and Indian influences in the shop. A Muslim, he became interested in Judaism as a boy helping his uncle sell postcards outside of Cohen’s shop. “Sarah never had children,” he says, “so I’m her children.”

Paradesi Synagogue, India’s oldest active synagogue, sits at the end of Mattancherry’s “Jew Town.” With the Jewish community dwindling in Mattancherry, the synagogue’s main visitors are now tourists, who arrive during opening hours, between 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day except Saturday.

Paradesi Synagogue, quiet after a day of tourists bustling in and out. At the front of the building, a sign asks visitors to remove their shoes before entering. Entering a synagogue barefoot is not a common Jewish practice; it's adopted from Indian traditions.

The last tombstone left standing in a Jewish cemetery in Mattancherry. Residences and streets were built on the cemetery over the last 50 years, reducing its once-impressive size.

Kadavumbhagam Synagogue peeks out from behind thick green vegetation. Josephai “Babu” Elias transformed the front room of the synagogue into a plant and fish nursery when he took the building into his care in 1977.

Fish swim in neon blue tanks just in front of Kadavumbhagam Synagogue’s glittering prayer hall.

Babu opens his prayer book and starts singing the prayer he said his grandmother made him sing before breakfast every morning. “We had to sing from here,” he says, turning three pages, “to here. And only then we could have breakfast.”

Ofera Elias, Babu’s wife, stands at her grandmother’s grave in the Ernakulam Jewish Cemetery. She points out the weeds growing tall around the tombstones. “No one is taking enough care of this site.” She says that in the absence of a Jewish community, she and Babu have made their own community of Hindu and Muslim friends.

Professor Karma Chandran stands in the empty Mala Synagogue, 50 kilometers from Cochin. He is fighting to preserve the Mala Synagogue and Jewish cemetery, two sites that have been heavily neglected for decades. When the Mala Jewish community migrated to Israel in 1955, they made a written agreement with the local government to protect the sites, but in 2012, the local government made plans to build a stadium on cemetery land anyway. Now, the blue-and-red stadium looms over the remaining tombstones, the stadium left empty and half-constructed because of ongoing court cases between the government and the departed Jewish community.